Scotland’s severed tongues

The Scottish Languages Bill aims to grant official status to Gaelic and Scots, enhance support for these languages in education, and address widespread ignorance about their historical and cultural significance in Scotland.

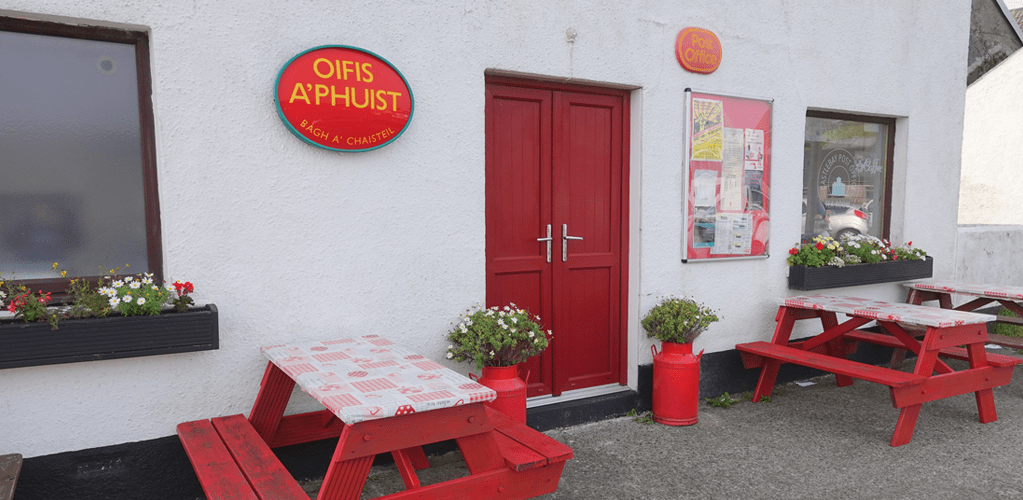

T he Scottish Languages Bill is currently winding its way through the Scottish Parliament. The Bill gives the Gaelic and Scots languages official status in Scotland and makes improvements to the support for the Gaelic and Scots languages in Scotland. This also includes changes in relation to Gaelic and Scots in Scotland’s education system aimed at promoting the languages and increasing support for them.

It is a measure of the shocking lack of institutional and governmental support for Scotland’s Indigenous languages that neither Gaelic nor Scots currently have official status and that Scots still lacks a commonly accepted written form despite the fact that it is still spoken by a significant proportion of the Scottish population and is understood by many more. Although Scots possess extensive literature, both in poetry and prose, has a previous history as the state and court language of Scotland when it was an independent state and is widely accepted by linguists as a language in its own right, many in Scotland still view Scots as merely a dialect of English, or worse as “slang.”

It is equally shocking that there remains widespread ignorance in Scotland about the former extent of Gaelic in the country or the role played by Gaelic in the creation of the Scottish nation itself. As I have previously pointed out, the Scottish nation itself is named after the mediaeval Latin term for Gaelic speakers, yet this basic fact about the origins of the Scottish nation remains little known in Scotland. Indeed, it remains commonplace to hear educated people who really ought to know better insist that Gaelic was never spoken in parts of Scotland where Gaelic language place names are thick on the ground, as we recently saw with Andrew Marr and his complaint about Gaelic language signage in Edinburgh Haymarket train station.

Making the learning of a language compulsory, more often than not, backfires and merely creates resentment; neither I nor most Gaelic or Scots activists propose making it compulsory for pupils to learn Gaelic or Scots in schools. However, one of the key goals of the educational system in Scotland should be to counter the appalling ignorance that is widespread in Scotland about Scotland’s indigenous languages and teach Scottish pupils the real facts about Scots and Gaelic, why the languages are culturally and historically important and why they are still important in modern Scotland. Doing so would increase the demand for Gaelic and Scots in education and cause more people to decide for themselves that they want to learn them. A motivated pupil is a better pupil.

Scotland has always been a multilingual country. As well as the three languages currently spoken in Scotland with an established history of intergenerational transmission within Scotland – Gaelic, Scots, and Scottish English – other languages have also been spoken over many generations by established populations in Scotland. These include Norse and its later development Norn, as well as Pictish and Cumbric.

Norse was brought to Scotland by the Vikings in the 800s and survived for almost a thousand years. Norse soon became the dominant language in the islands of the West of Scotland, where it was spoken by a mixed Norse-Gaelic population; hence the traditional Gaelic name for the Western Isles, na h-Innse Gall, ‘the islands of the Foreigners’. In Lewis and Harris, the vast majority of place names are Norse in origin, and it is one of the ironies of Scottish linguistic history that when Gaelic was the dominant language of much of Lowland Scotland, the modern heartlands of the Gaelic language were Norse-speaking.

Gaelic-Norse bilingualism appears to have been widespread in northwest Scotland and the islands in the Middle Ages. Eventually Gaelic reasserted itself, it is unclear when Norse finally died out in the north west and the Hebrides but it seems to have vanished by the early 1500s if not before.

Norse survived much longer in the Northern Isles, where Celtic speech was completely replaced by Norse in Viking times. A trace of the previous Celtic inhabitants remains in the name Orkney, which derives from a Celtic word orko, meaning boar, probably a Pictish tribal name. Orkney and Shetland famously remained politically linked to Scandinavia until 1468 when the Northern Isles pledged by Christian I, in his capacity as King of Norway, as security against the payment of the dowry of his daughter Margaret, betrothed to James III of Scotland. However, the money was never paid, and the islands became part of Scotland in 1472.

The islands remained Scandinavian in language for several centuries, although, by this time, the Old Norse of the Vikings had evolved into a different language called Norn. Norn survived in Orkney until the late 1700s and in Shetland until the early 1800s. Although it left abundant traces in the form of place names and words borrowed into the Orkney and Shetland dialects of Scots, there are few surviving texts in Norn, making it difficult to reconstruct the language accurately in order to revive it. Nevertheless, attempts have been made, although given the huge gaps in the attested records of the language, these necessarily involve considerable educated guesswork.

Pictish was the Celtic language which was widespread across Northern Scotland – including Orkney and Shetland – prior to the later spread of Gaelic and Norse. It was once thought that Pictish comprised, at least in part, a pre-Celtic language spoken by the most ancient inhabitants of Britain, but this theory is now out of favour.

It is now thought that Pictish derived from the northern extension of the same Brittonic Celtic language whose more southern varieties gave rise to Welsh, Cornish, Breton, and Cumbric. Pictish came from those varieties of Brittonic Celtic which became isolated from the rest of Brittonic by the Roman occupation of Britain. Pictish thus escaped the massive influence of Latin which affected most of Brittonic. This influence even extended to basic vocabulary, the Welsh and Cornish words for fish pysgodyn and puskes respectively, come from the Latin pescatum whereas Gaelic, descended from a form of Celtic spoken beyond the Roman Empire, preserves the Celtic word for fish, iasg.

Pictish most likely did not contain as many Latin words as more southern forms of Celtic, but it seems that the Picts maintained close ties with their fellow Celts in Ireland, who were likewise beyond Roman control. The Picts adopted the Ogham alphabet used for Archaic Irish, and the two dozen or so Pictish inscriptions written in this script, consisting of a series of notches and dots, represent the oldest known writing in Scotland. Ogham inscriptions are hard to read at the best of times, the Pictish Ogham inscriptions are the only known examples of Ogham being used to write a non-Gaelic language and as such are especially difficult to interpret.

It seems that Gaelic spread in Northern Scotland along with Christianity, but it is highly likely that Gaelic had already substantially replaced Pictish throughout most of Pictland long before the Picts and Scots united to form the kingdom of Alba under Kenneth MacAlpine in the 840s. It is unknown when Pictish finally died out, but it was probably gone by around the year 1000. Reviving Pictish is impossible. The language survives only in a few meagre linguistic scraps in place and personal names, often of uncertain meaning. No connected texts survive, and nothing can be said for certain about basic aspects of Pictish grammar. We know nothing about verb structure, pronouns, pluralisation, or numerals in Pictish, essential parts of the workings of any language. Pictish is a fossil language and the surviving fossils are particularly few.

Cumbric was the Celtic language of Southern Scotland. Even though the Romans did not maintain their occupation of Southern Scotland for long, quickly retreating to Hadrian’s Wall after an abortive attempt to establish the northern border of the empire along the line of the Antonine Wall, the Celts of Southern Scotland remained in Roman political and cultural orbit and maintained close links with their relatives further south.

These links were sufficient to ensure that the Celtic language of Southern Scotland evolved in tandem with the Celtic of Roman Britain, maintaining their cultural ties to the Celts of Wales and the Celtic-speaking lands known to the Welsh as the Hen Ogledd, the Old North.

One of the oldest surviving Welsh poems is The Gododdin, which tells the story of a raid undertaken by the warriors of Gododdin, modern Lothian, against the Saxons who were then penetrating Yorkshire. Gododdin is the Welsh form of the tribal name Votadini, recorded by Roman authors as inhabiting Lothian. The difference in form between Votadini and Gododdin gives you an idea of the massive phonetic changes experienced by Celtic in the later Roman era. Gaelic also underwent massive changes, albeit different from those found in Brittonic. The outcome of these changes resulted in the two modern branches of Celtic, Brittonic and Goidelic, looking very different from one another even though they had been very similar at the time of the Roman Conquest of Britain. Pictish will have undergone phonological changes of its own, but very little is known about these.

The poem The Gododdin survives in Mediaeval Welsh, later generations of copyists modernised the text so it does not represent the Celtic language of Southern Scotland in which it was probably composed originally. This language is known to linguists as Cumbric. Like Pictish, Cumbric survives only in a few meagre linguistic scraps in place and personal names. Deriving from northern varieties of Brittonic, which did not survive in Wales and spoken as it was in a very different linguistic environment from Welsh, in close contact with Gaelic and with Norse in South West Scotland, Cumbric must have evolved along distinct linguistic lines of its own even though its speakers identified themselves as ethnically and culturally the same as the Welsh. However, we know next to nothing about the ways in which it differed, as it must have differed, from the language spoken in Wales.

Cumbric clung on in parts of the Scottish Southern Uplands until the late 1100s or early 1200s, becoming extinct after the incorporation of the semi-independent kingdom of Strathclyde into Scotland in the early 11th century. William Wallace’s ancestors seem to have been Cumbric speakers. Wallace was an older Scots term for Cumbric speaker. No known contemporary written texts in the language survive. However a mediaeval Scots Law from the time of King David I (1124-1153), Leges inter Brettos et Scottos, ‘Laws of the Brets and Scots’ seems to suggest that Cumbric speakers still survived as a recognised community in Scotland at the time the law was decreed. This law contains three apparently Cumbric words, mercheta (cf. Welsh. merch, ‘daughter/girl’), galnys (cf. Welsh. galanas, ‘murder/blood-money’) and kelchyn (cf. Welsh. cylch, ‘circuit/circle’).

Scottish place names derived from Cumbric include Glasgow from Glas cau – green hollow, Bath gate from Baeddgoed – boar wood, Lanark from the Cumbric cognate of Welsh Llannerch – thicket, Penicuik – compare Welsh Pen y gog – hill of the cuckoo. There are many more.

Like Pictish, Cumbric cannot be revived as too little of it survives, yet it tells us of Scotland’s close ties to Wales and is an important part of Scotland’s story.

Cumbric, Pictish, and Norse are three of Scotland’s tongues which have fallen silent, severed long ago, but Gaelic and Scots are speaking still. The Scottish languages bill aims to ensure that they will still speak to generations of Scots yet to come.

GOING FURTHER

Scottish Languages Bill | SCOTTISH PARLIAMENT

Andrew Marr, Gaelic and Scots | PUBLIC SQUARE UK

[Read our Comments Guidelines]