The day the country turned on the Tory Party

Brexit, barely discussed during the general election campaign yet ever-present, catalysed the Tory downfall, culminating in a significant vote share drop. The new Labour government faces challenges, but now is a moment to celebrate the defeat of a damaging political ethos.

S o it’s over. From the beginning it has been strange. In my blog first post of the campaign I noted that for months this election had seemed overdue, but its sudden announcement made it seem premature. Very quickly what was both long-awaited and novel seemed to have become interminable. From the start the outcome seemed predictable, and yet until the very end important aspects of the outcome remained highly unpredictable. And, throughout, little was said about Brexit, and yet Brexit in some form or another was a constant sub-text.

What is also over is the nine-year period of Conservative government, or 14 years including the Conservative-led coalition. For many of us that, just in itself, makes it a moment to savour, whatever we may think of the incoming government or of its prospects. It is not even necessary to be especially left-wing, or left-wing at all, to feel some sense of relief, if only exhausted relief. For, by any standards, these have been tumultuous years, and in all too many ways calamitous years. So it’s worth, in this moment, briefly taking stock of them.

Goodbye to all that

Politics isn’t just about political leaders, by any means, but it is partly about them and, anyway, thinking of it in those terms can be a useful shorthand. We know, roughly, what it means to talk about the Thatcher, or Thatcher-Major, period, or about the Blair, or Blair-Brown, period. And we can grasp something of what we have just lived through simply by the length of describing it in that way: the Cameron-May-Johnson-Truss-Sunak period. It discloses the churn, the instability, the failure; the lack, in fact, of conservatism in its most general sense.

But it gets far worse if we consider each individual element. Cameron, entitled, patrician, casually corrupt and yet, possibly, the least awful of them. May, stiff, unimaginative, perhaps dutiful, but that duty spotted through with cruelty and spite, and yet, possibly, the least immoral of them. Johnson, depraved, venal, priapic, lazy, dishonest in every conceivable respect and yet, possibly, the most imaginative of them. Truss, woefully incompetent, vain, ideologically rigid and yet at least the most short-lived of them. And Sunak, whose plastic surface concealed only more plastic, an emptiness inhabited only by an ambition to be ambitious and yet, in inconsistent flashes, perhaps the most pragmatic of them.

Taken in total, even without considering the bottomless pit of their grueseome camp-followers and underlings, they form an unprecedented cast of political and psychological grotesques paraded in unprecedentedly quick succession. Together, they left a legacy of damage, disgrace, decay and, ultimately, disgust. If this election result tells us anything it is that, collectively, they managed to turn those of just about every shade of political opinion against them. Even those who did vote for their party yesterday will, in many cases, have done so with huge reservations and little enthusiasm. So, just at the most basic level of politics, they have comprehensively failed. If there is nothing else to say now it is that we, as a nation, are unequivocally better off for having seen the back of them.

Our voting system is difficult to defend on rational grounds and yet, sometimes, it does manage to capture, and in that sense to represent, the state of the nation, if only despite, rather than because of, itself. Thus the 2017 election gave rise to a parliament which, like the country, was deeply and almost evenly divided by Brexit. The 2019 election expressed a national desire, reprehensible and illusory as in my view it was, and partly born of exhaustion and boredom, for Brexit to be ‘done’. This latest election has shown a kind of national consensus, even if based on a wide variety of reasons, that the Tories needed to be routed. There are endless statistics being bandied around this morning, but the key one is this: the Tory share of the vote dropped by almost 20 percentage points.

Brexit: cause and consequence

Brexit is a central cause of what has happened to the Tories. What would have happened but for Brexit is, of course, unknowable, but it was certainly the referendum vote which caused Cameron to resign, and it is all but certain that there would not otherwise have been the same turnover of leaders. Some of them would certainly not have ever become Prime Minister without it. The Partygate scandal may have been the beginning of their end but, as I’ve written elsewhere, there are many links between that and Brexit. Subsequently, and perhaps the decisive moment from which the result has flowed, came Liz Truss’s mini-budget disaster, which is absolutely inseparable from Brexit. And, of course, for many voters, Brexit is the direct cause of their revulsion at the Tories: an unforgiveable, era-defining disaster in itself, even before the Tory attack on the middle-classes and established institutions which it unleashed, as discussed in last week’s post.

But Brexit is also the consequence of these years of Tory misrule. Between them, the leaders and their regimes did not just bring Brexit into existence, they also gave it its particular shape. By that I mean not simply the institutional form it has taken, but much of the dishonesty, division and toxicity which has surrounded it, and which has also created the situation whereby very little can be done about it, at least for now. For, whilst this is indeed a moment to savour and to take stock, this election is also, as I have been trying to stress in my last few posts, only a staging post within the still-unfolding politics of Brexit.

That’s not the statement of a ‘obsessive remoaner’ who can’t ‘let go’, and wants to ‘re-litigate the referendum’ or even ‘go back to 2015’ (all things which I have been wrongly accused of). On the contrary, it is an acknowledgement of what Brexiters ought to be saying: Brexit wasn’t just a passing event, now finished with, but the beginning of a new era. Indeed it’s not just what Brexiters ought to be saying, it is what they would be saying were it not that they know it has failed. Had it been even remotely a success, they would certainly be more than happy to acknowledge that we are living in a country transformed by its consequences.

So if the election is a post-Brexit staging post, what happens next? That can be thought of in two ways. One is about policy and, specifically, how the Labour government will approach the UK-EU relationship and, equally important, how the EU will approach relations with the UK’s new government. The other is about Brexitism, and the fall-out of this election result for the Conservative Party and the political right generally.

What next? #1 Labour’s post-Brexit policy

I’ve already written a lot about this in my column, and my summary of what can be expected was published last month in Byline Times. Other, perhaps more expert, summaries are widely available, including a wide-ranging analysis from the Centre for European Reform, a mainly economics-focused piece from the Financial Times, and a specialized assessment of trade issues by Sam Lowe on his Most Favoured Nation newsletter. We will soon know the realities, so I don’t see much value in speculating further on this question, but two specific points may be worth making.

One is that, as of now, the dynamics of the domestic politics around the relationship with the EU have fundamentally changed. That is because almost all of the most influential pressure on the government will be pushing it towards a closer, and certainly a more amicable, relationship with the EU, ranging from pressure to maintain regulatory alignment right through to pressure to rejoin the single market and customs union. That is in complete contrast to the last eight years where the government was constantly under pressure from its backbenchers, and pro-Brexit media and thinktanks, to diverge from the EU and to have as antagonistic a relationship as possible. It’s true that those voices will still exist and be very noisy but, overnight, they have become far more marginal to where political power and influence lie, for all that Farage’s election will give him a new platform to pollute the airwaves.

The second point is that, from now on, many people are going to start (some, no doubt, have already started) saying that Labour would have won, and won big, whatever their policies, and therefore they could and should have been far bolder in their promises. That will be said in relation to all kinds of issues, as it was after the 1997 election, but I’m obviously meaning, in particular, that it will be said in relation to reversing Brexit (or reversing hard Brexit). So it is perhaps important to recall, before it recedes too far into memory, that this was not obvious at the time that Labour formulated their post-Brexit policy, and that many, even most, commentators did not expect the opinion poll lead to hold up all the way through to the election as it did. And, indeed, had Labour changed Brexit policy in the run-up to the election that might well have changed the outcome entirely, or at least the extent of the victory. We will never know, now, but it is far easier to be wise with the result in, and the ‘Ming vase’ safely carried over the victory line.

Similarly, it should not be thought that, with a huge victory now achieved, changing that policy in any substantial way would be risk free. The size of the majority makes no difference (despite all the recent Tory nonsense about a ‘supermajority’, as if it bestowed extra powers on a government). Labour’s voter coalition is a fragile and not very deep-rooted one, achieved primarily because of the extent of anti-Tory feeling, and reliant on the ‘efficiency’ of their vote-harvesting, which has partly been achieved by its very limited, and highly muted, post-Brexit policy.

That said, the very fragility of the voter coalition means Labour will be under huge pressure to quickly achieve economic growth, with all that would enable them to do, and one solution (though it wouldn’t be that quick to achieve) might be to seek single market membership. Having been so adamant that they will not do so, I think it almost inconceivable that they change tack, but many will no doubt urge it to do so, and this will also have a new dynamic now. For, unlike the Tories, such urgings will be coming from within the party and be being resisted by a leadership which, whatever it may say, is not ideologically invested in Brexit.

In immediate practical terms that may not seem like much of a difference, but the ‘join the EU movement’ is now in a different place to that which it has been at any time since the UK left, in the sense of being strongly represented within the governmental tent (not to mention having significant increased parliamentary representation from the LibDems). If joining the EU is ever to happen, this movement has a better platform to build on now, certainly compared with what would have been the case had the Tories won. At least for now, the wilderness years are over, and if public opinion for re-joining continues or even increases, the case will become progressively harder to ignore.

What next? #2 Brexitism and the Tory meltdown

So what of the departing Conservatives? I wrote recently that in some ways this election could be read as a verdict not so much on Brexit, but on Brexitism. It was found guilty, including of the way it has corroded standards of public life, the restoration of which is an immediate and urgent task for the new government. But as I said in that post, Brexitism will not be killed off by this election and, paradoxically, the heaviness of the Tory defeat and the scale of the Reform vote (these things being linked, of course) will mean that, where it lives on, it does so as undiluted faith of its most hardcore believers.

Inevitably, there is now going to be an intensely bitter period of recrimination within the Tory Party and on the political right generally. It will not just be about the election result, but about the entirety of recent political history, going back to the referendum. It will be about Brexit, to a large extent, but not about its fundamental wisdom. Rather, it will be about Brexit not having been done ‘properly’, or its ‘opportunities’ having been squandered. What the Tories ought to consider, but probably won’t, is the underlying, historic folly of having held a referendum in 2016 to defuse the threat from Farage, and ending up with him still biting deeply into their vote, but now also having the LibDems on their one-nation flank, digging very deep into their traditional heartlands. That’s the meta-story of the last decade and it’s not clear how Humpty-Dumpty can be put back together again.

As early as February 2023, I wrote in detail about what was in store after this election, because it has been obvious for at least that long, including the significance of Reform being “able to mobilise perhaps 15% of the electorate, mainly at the Tories’ expense” (it turned out to be 14.3%). Barring some details, almost every word of that post still applies now, and so do those of a more recent post, last October, after the Tory Party conference. There, I discussed how Brexit has morphed into Brexitism and has driven the Tory Party mad. I won’t repeat the very lengthy analysis of those two posts, which are there to be read if anyone wants, but the point is that now, like a boil that has been bulging with festering yellow pus, all this madness is about to explode.

The result of that will partly depend on exactly who is left in the House of Commons when the dust settles, and whether the party amends its leadership selection system so as to remove power from the rank-and-file membership. But there must be a strong expectation that the initial move will be to chase the Reform vote, lurching to the purism of National Conservatism, even though some of its key advocates lost their seats.

Meanwhile, Reform itself has created, for the first time, a bridgehead of avowedly populist MPs in the House of Commons. It will be used and abused by Farage just as he used his position as an MEP in the European Parliament, and it is depressingly easy to imagine the media continuing to shower disproportionate attention on his antics, well beyond what Reform’s four seats warrant, for all that Farage will brandish their vote share as a weapon. The longer-term question is whether that vote share is its floor or its ceiling and, especially, whether, as Farage has already threatened, they will now be able to move from poaching disaffected Tory voters to making inroads into the traditional ‘old Labour’ vote. To the extent that Starmer has stabilized that vote, by nullifying Brexit as an issue and the more general revamping of his party, it feels remarkably fragile. It’s not so hard to see the Red Wall falling again.

For the time being, what happens on the political right may seem quite marginal to politics. All the focus will be on the Labour government and what it is doing. But that won’t last forever, especially if that government falters, and the 2029 election approaches with a mood of public dissatisfaction not just with Labour but with politics generally. Then, the anti-politics of a Brexitist party may become very attractive to many voters, and it can’t be assumed that such attraction will not extend to newer, younger voters by then.

In fact, for all the scale of Labour’s victory, I can’t shake off a sense that it is, in its entirety, fragile, and certainly more a vote against the last government than for the new one (especially in England and Wales). Of course, it is a remarkable achievement. Who would have thought, five years ago, that such a huge Labour victory was possible, or even a Labour victory at all? That achievement isn’t negated by the relatively small vote share, to the extent that one of the main reasons why Tory seats were flipped by the LibDems in this election, when they weren’t in 2019, was because voters in those seats no longer feared a Labour government. But the victory also speaks of a huge volatility so that, by the same token, who would want to bet on what may happen in the next five years? That’s an important question for all of us, and in the context of Brexit, or more precisely for those who would want to see its reversal, it is also an important question for the EU.

A day to hope

But I wouldn’t want to end this piece on so sober a note. This is, indeed, a day to savour. There may be, there will be, disappointments, and perhaps worse, ahead, but now there is something to celebrate. It isn’t simply the defeat of a political party. It is the defeat of a political ethos of gross dishonesty, unforgiveable incompetence, corruption, entitlement, and cruelty. That ethos has degraded our institutions, poisoned our political culture, and debased our international reputation. It gave us Brexit, of course, but it also gave power to mediocrities, dullards, charlatans, fantasists, fanatics, thugs, and liars.

For all that we will have had a very wide and contradictory variety of interpretations of what we meant by it, yesterday, with our stubby pencils, in rickety booths in makeshift halls across the country, we collectively and clearly said: we should be better than this.

Let’s hope we will be.

Sources:

▪ This piece was first published in Brexit & Beyond and re-published in PUBLIC SQUARE UK on 9 July 2024 under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. | The author writes in a personal capacity.

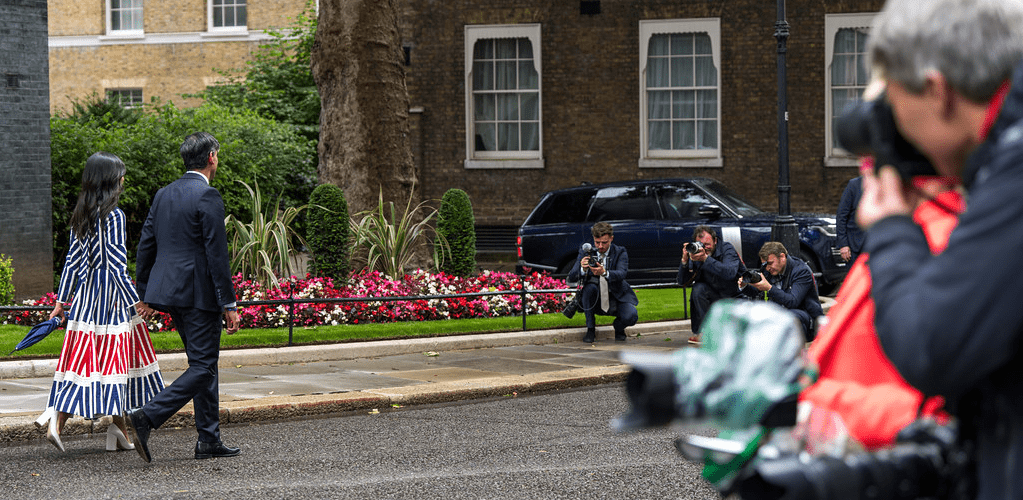

▪ Cover: Flickr/The Conservative Party. (Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.)

[Read our Comments Guidelines]