Too often learning ‘British history’ means learning ‘English history’

If history is to be of any use to those who study it, it ought to help them understand the nature of the country and society they live in.

If history is to be of any use to those who study it, it ought to help them understand the nature of the country and society they live in.

H ow much do you really know about the history of the United Kingdom? What passes for “British history” is, all too often, merely the history of England with bits of the histories of Scotland, Wales and Ireland tacked on when they affected events in England.

In a radio interview some years ago, the BBC presenter Nicky Campbell put it to me that, fun though the Romans or Tudors might be, only history nerds are interested in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. “You say that because you’re in London,” I replied. “You wouldn’t say it if you were in Belfast.”

It only takes a short stroll through Belfast to see why. Unionist streets are famous for their colourful murals of the protestant hero William of Orange riding his white horse into battle above the words: “Remember 1690!” That was the year of his victory over the catholic James II at the Battle of the Boyne.

The events of 1690 are still a sensitive topic in Northern Ireland, but they’re largely unknown in the rest of the UK. Any Scot knows about the controversial passage of the Act of Union in 1707, creating the joint kingdom of Great Britain – but very few people in England have even heard of it because it is hardly ever taught in schools.

School constraints

Part of the blame lies with educational tradition. It is quite normal for any country’s educational system to give priority to its national history. This has remained central to government thinking ever since the introduction of the national curriculum at the end of the 1980s. But what counts as “national” in a composite country like the UK?

Teachers in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland have long tried to balance the history of these nations with that of England. But for teachers in England, the problem is compounded precisely because England dwarfs the other nations in size and population. Many history textbooks make use of examples from other parts of the UK to illustrate common themes, but it is unusual for English schools to spend much time studying Scottish, Irish or Welsh history in its own right.

Does this matter? According to the TV historian David Olusoga, it does. He has promoted his new BBC television series, aptly named Union, by calling on schools to teach more about the histories of the other nations of the UK, especially if we want the union to continue.

With timetables heavily constrained, few history teachers will be able to rise to Olusoga’s challenge, especially with the requirement to balance the demands of British history with the need to teach about non-British and non-Western themes. Many schools now spend more time on the history of India or China than on the history of Scotland or Ireland.

In any case, most children in England drop history at 14, and at GCSE and A level the choice of topic is determined far more by examination boards and by what teaching materials are available than by ideals and aspirations.

The role of broadcasters

If people are to learn more about the different histories that make up the United Kingdom, it might be better to make more creative and extensive use of broadcasting and other media outlets rather than imposing yet another initiative on overburdened schoolteachers.

However, the ideal of a British history that gives a proper space to the histories of all parts of the United Kingdom is too important to be overlooked, especially at a time when there is much more of a drive to make history at school and university more global in its outlook.

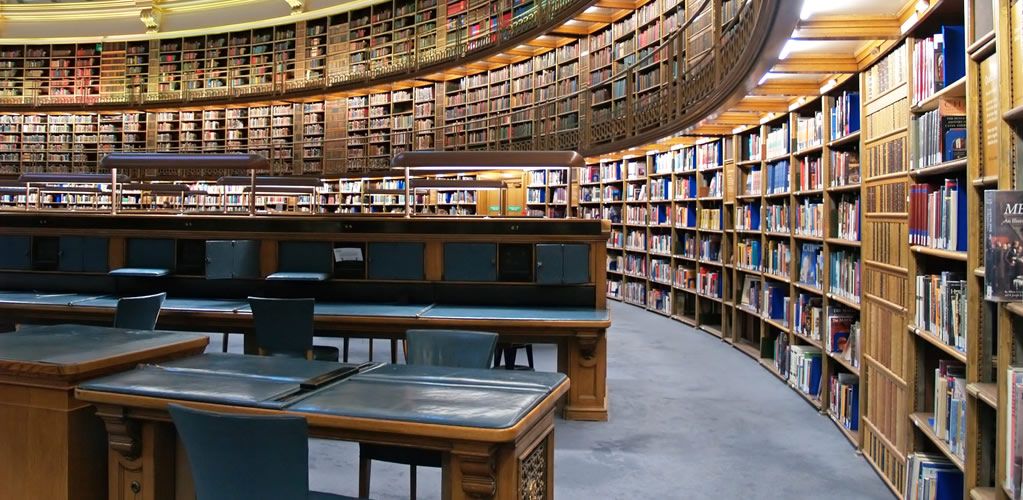

At Anglia Ruskin, where I am a lecturer, we have for some years now taught a course on the Tudor and Stuart period which gives students a good grounding both in familiar themes from English history and in Scottish and Irish history.

Students learn about the flourishing of the Scottish Renaissance looking at Stirling Castle as well as Hampton Court, and about the doleful impact of English rule on Ireland, from the rebellion of “Silken Thomas” against Henry VIII, the Ulster Plantations and the harsh Cromwellian settlement, to the arrival of William of Orange and his victory in 1690.

It is not easy to fit everything in, but if history is to be of any use to those who study it, it ought to help them understand the nature of the country and society they live in. The Northern Ireland Brexit Protocol and the continuing saga of demands for Scottish independence remind us that these histories should not be of interest only to nerds: we all need to know them.

GOING FURTHER

UK schools should teach all four nations’ histories, says David Olusoga | The Guardian

Union with David Olusoga | BBC Two

[Read our Comments Guidelines]