Why the UK’s wealthiest 10% are turning their backs on the rest of society

You may feel little sympathy for people in the top bracket of earnings, but don’t let that stop you from reading. Like it or not, their views and actions matter to everyone.

You may feel little sympathy for people in the top bracket of earnings, but don’t let that stop you from reading. Like it or not, their views and actions matter to everyone.

R ecently, there seem to have been a lot of people like William, in privileged jobs and on six-figure salaries, complaining that they’re “struggling” – including to the Times, the Independent, the Mail and the Telegraph.

“I feel fairly middle of the road and average, but objectively I know this is completely untrue. I am at the top of the income percentiles – though I also know I’m miles away from the very rich. Everything I earn goes at the end of the month: on school fees, holidays, and so on. I never feel cash-rich.”

— William, City firm director in his 50s

Perhaps you recall the BBC Question Time audience member who, weeks before the 2019 general election, couldn’t believe that his salary of over £80,000 made him part of the top 5% of UK earners – despite the UK being a country where almost a third of children live in poverty.

You may instinctively feel little sympathy for these high earners, but don’t let that stop you from reading on. Their views and actions should matter to us all. Like it or not, they have disproportionate political influence – representing a large proportion of key decision-makers in business, the media, political parties and academia, not to mention most senior doctors, lawyers and judges.

And in their private lives and behaviour, more and more of this group appear to be turning their backs on the rest of society. When interviewing them for our book Uncomfortably Off: Why the top 10% of Earners Should Care About Inequality (co-authored by Gerry Mitchell), we heard repeated concerns about the threats now posed to their lifestyle and status. This is from people who, while a long way from the UK’s “super-rich”, enjoy far more wealth and privilege than the majority of the country.

We also found misperceptions about wider UK society were common among this group – for example, that state social spending is higher than in other countries, that people in poverty and receiving the most from the state are largely out of work, and that they, as high earners, do not benefit as much from the state as those on lower incomes, forgetting how much they rely on the state over their lifetimes.

And we often saw a distance between the worldviews expressed by many in the top 10% and their own actions. For instance, many say they have strong meritocratic beliefs, yet are increasingly reliant on their assets and wealth to secure advantages for themselves and their children, meaning inequalities among millennials and younger generations will become more dependent on inheritance. Such thinking was captured by a recent Telegraph article that declared: “No more rags to riches – family money will be the key to getting wealthy.”

The environment is another area where thoughts and actions often diverge among this high-earning group. While worrying about the environment is positively correlated with income and education, research also shows that the higher your income, the higher your carbon footprint.

One potential endpoint is a world of bunkers, without trust or a functioning public realm, where we all declare one thing and do another without much heed to the common good. But increasing inequality doesn’t just threaten those in poverty – it negatively affects the whole of society. It means higher imprisonment rates and more expense devoted to security, more mistrust in everyday interactions, worse health outcomes, less social mobility and more political polarisation, to mention just a few of these effects.

This is the road we are on, with UK inequality levels projected to reach a record high in 2027-28. Can anything be done to encourage the UK’s highest earners to recognise that their best hope of a happier, healthier, more secure future – including for future generations of their families – is by working with society as a whole, not turning their backs on it? Or is it already too late?

Launch video for the book Uncomfortably Off.

Who’s in the top 10%?

“If you’re in a privileged position, and all your friends are from a similar background, then you don’t think about inequality on a day-to-day basis.”

— Luke, young strategy consultant for a Big Four accounting firm

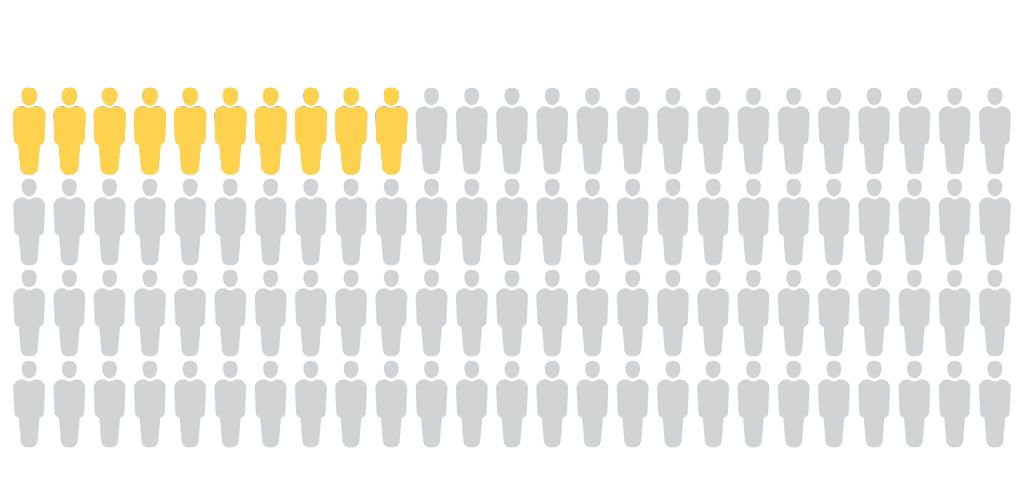

In the UK, the threshold for the top 10% of personal income before tax is £59,200, according to the HMRC’s latest statistics. This is over twice the median wage, which is generally under £30,000.

But the top 10% incorporates a wide range of incomes. Accountants, academics, doctors, civil servants and IT specialists are still typically much closer to the UK’s median wage than the poorest members of the top 1%, who earn upwards of £180,000. The higher you climb up the distribution ladder, the larger the distance between the steps becomes, which is perhaps why a 2020 Trust for London report found little agreement on where the “riches line” is – defining who, exactly, is rich and who isn’t.

The way we think of richness is generally absolute rather than relative. Images of Lord Sugar, Donald Trump and the characters of Succession come to mind – along with Ferraris, caviar and private jets. Such thinking may explain why some in the top 10% agree with the principle that the rich need to pay more tax, but do not think it includes them.

And while this is a diverse group, they still share many characteristics. The majority are men, middle-aged, southern, white and married. Members of the top 10% are more likely to own their home or have a mortgage. More than 80% are professionals and managers, and over 75% hold a university degree.

Just as they’re sociologically characterised by their education and occupation, high earners usually define themselves by hard work. After telling us they “didn’t feel rich”, most would admit they were in some way “privileged” – then follow that with a declaration of having “worked hard” to get there. Most clearly feel they’ve earned their privileged position, and that “life is fair”.

At the same time, even though they define themselves through their graft, many high earners don’t think their work is particularly meaningful.

Susannah, who is in a very senior position at a large bank, was blunt about the contribution of her work to society at large:

“[Laughs]: Not much really … Well, I suppose you could say that I’m helping to make sure the bank are spending efficiently. They’ve got a huge customer base globally, so we’re helping deliver products at a more affordable price and the customer service they get around that is better. But if I compare that to my husband’s contribution as a [public sector worker], his is way more.”

The more that someone’s position is based on being able to distinguish themselves from others – be it through the accumulation of money or “cultural capital” – the less incentive there is to socialise with others who cannot meet this criterion of what is valuable.

Luke spent the first part of his life in a private school, enlisted in the army, then attended Oxbridge. He was later a teacher in the Teach First programme, before starting work as a consultant. He told us that his background meant he doesn’t really think about inequality on a daily basis. He comes from a privileged upbringing and all his friends do too. He does not interact with anyone outside his socioeconomic group, although he did when he was a teacher, commenting: “It was clear I was teaching kids with very different lives.”

An exception among our interviewees was those who had experienced upward mobility. Many of them answered that they did know people who were significantly less wealthy, and who still lived in the place from which they had “escaped”.

Gemma, a consultant with a £100,000+ income in her late 30s, moved from the north of England to London. She told us:

“You don’t know what people earn in London. My closest friends tend to be people I’ve worked with, that’s just how it’s turned out, so you’re meeting people at around the same economic level. At home, I know what people do and how much they earn.”

In the UK, the threshold for the top 10% of personal income before tax is £59,200, according to the HMRC’s latest statistics.

How the top 10% feel about the world today

“As I’ve started to earn more and worked hard for it, I care more about the tax I pay. I didn’t think about it when I was younger … But now I’m more aware of it and how it’s helping society.”

— Louise, sales consultant for a global tech company in her 40s

When we asked Louise about inequality, the less well-off and whether the rich should do more, her answers were broadly the same as we would give: inequality is detrimental to society and not inevitable; those in poverty struggle because of circumstances beyond their control; the rich should make much greater efforts to address inequality. However, when asked which political party she voted for in the last election, she responded: “The Conservatives.”

The obvious question we should have asked next was, why? But for some reason, we let the silence linger – until Louise’s voice cracked slightly. “The tax issue,” she said. “Protecting high earners.”

Like so many of the “uncomfortably off” we interviewed – including members of the top 10% by income in Ireland, Spain and Sweden – Louise did not think of herself as rich. She agreed there should be more redistribution and more help for those worse off in society, but she didn’t agree it should come out of her taxes. This was not an uncommon view among our interviewees:

“If I’m contributing to people who are below the poverty line, fine. But if I’m funding people who are sitting at home and don’t want to work, then I’m not happy about it. Do I want taxes to go up for higher earners? No, I pay more than enough.”

— Sean, small business owner in his 40s with a top 1% income

Our interviewees often don’t think of themselves as beneficiaries of public policy, and tend to think state action is, almost by definition, overweening and invasive – forgetting the myriad ways that all of us depend on public infrastructure and on underpaid key workers. This even applies to those who, like Sean, do not come from wealthy families themselves.

Whenever they can afford it through their own spending or as a perk from employment, high earners in the UK are increasingly relying on the private sector, especially as they see the public sector as crumbling and inefficient. The more they do so, the less likely they are to associate paying tax with something that benefits them directly and to trust public solutions to public problems.

Sometimes, this withdrawal into the private realm is justified as a progressive stance to protect others.

Maria, a marketing director in her 40s, told us, regarding her recent decision to use private education and healthcare for her family:

“I’ve decided to go private to give my space to someone else. The government wants us to do that – why else would they be advertising that there are no doctors?”

Cracks in the narrative

“I worry about my kids. I don’t know what they’re going to do because of all the jobs – and I say this from a financial services background – a lot of the entry-level jobs have been moved offshore. The job where I started [at an accountancy firm] is now done in India, and has been done in India for some years … So it’s harder to break into those industries.”

— Susannah, works in an international bank with a top 1% income, in her 40s

As a rule, the UK’s highest earners appear relatively pessimistic about their country’s future, but quite optimistic about their own. This signals a tacit distance between how they see their lives and the fate of the rest. However menacing and huge the challenges of climate change and inequality might be, many are confident they will still manage to do well. Politics, as terrible as it is at the moment, mostly happens to others.

However, cracks are starting to appear in this narrative. We conducted a first round of interviews between 2018 and 2019, and a second in early 2022. During the first round, many in the top 10% said they worried that their children would not be able to climb the professional ladder as they did. They had seen a decline in the status of hitherto solidly middle-class professions that now appear in turmoil, such as barristers, doctors, and academics.

Respondents such as Susannah were starting to observe that the link between hard work, education and pay might be weakening as middle-class jobs are being hollowed out, threatened by automation, offshoring and precarisation.

During the second round, the cracks appeared even wider. Amid the Ukraine invasion and with inflation rising sharply, many told us they had started feeling the pinch themselves – especially those who relied more on their income than on savings and assets. For some, the private fees required to remain in the same circles as the UK’s wealthiest, and for their children to have a fighting chance of the best jobs of the future, appeared at risk of falling out of reach.

According to the Resolution Foundation, UK citizens are living through the worst parliament on record for household income growth. Meanwhile, as the economist Thomas Piketty has long argued, the preeminence of capital over wages is only becoming starker.

In such circumstances, what should high-income earners do? The most obvious answer is to turn as much of their income as possible into assets, in an effort to insulate themselves from inequality: to move away, to hoard, to guarantee advantages for their children. In the pursuit of all of that, tax is just a burden, rather than a potentially progressive tool for the benefit of society as a whole. This is in some sense rational. High earners can see that income from assets is not taxed in the same way, and fear the impact of redistribution on the capacity to pass on privileges to their children.

The top 10% may be floating away in their own socio-economic bubble, but this strategy of social distancing may ultimately prove ineffectual. Inequality doesn’t just threaten those in poverty but affects the whole of society, whether through an increase in, for example, imprisonment rates, a greater burden on the health service (including higher levels of mental illness), or living in less functional and cohesive communities.

Even those who recognise the dangers – and long-term unsustainability – of isolating and insulating themselves from wider society struggle to find a palatable alternative. Having been raised to see individual hard work as the solution to most things, the combined challenges of AI, global warming and the gig economy – coupled with increasing concentration of wealth at the very top – makes the world a confusing place for many high earners.

Danny Dorling, professor of geography at the University of Oxford, discusses the global super-rich.

‘Everyone became polarised’

The austerity measures adopted by the UK government since 2010 have done very little to increase investment and economic growth. According to inequality expert Gabriel Palma, the UK, like many other rich economies, is undergoing a process of “Latinamericanisation” – of “relentless inequality and perennial underperformance”.

Despite this, the UK’s relatively high earners have, until recently, been mostly insulated from the worst effects of inequality. Their share of national income has grown in the past few years while that of most people has declined. Yet some we interviewed said they were feeling the political effects of a more unequal and polarised society, describing politics today as “extreme” and appearing nostalgic for a lost “centre ground”. Tony, a senior IT manager told us:

“Everything now is ‘far’ [left or right] – what’s happened to the centre group? It’s not just in politics, it’s in every area of life. There’s nowhere everyone can meet … The age of debate is disappearing. The age where you could persuade people of your opinion has gone. I don’t know when it happened – everyone became polarised.”

Yet the reality is their policy preferences still tend to coincide with policy outcomes much more closely than other income groups. We summarise these preferences as “small ‘l’ liberal” in two key aspects.

First, we found that most high earners intuitively hold an individualised worldview in which everyone is responsible for his or her own actions, and should be left alone as long as they don’t hurt anyone else and can prove that they can support themselves and their families. Through their educational and professional successes, they have managed to attain such a position for themselves so it follows that they should have the prerogative to be left mostly alone. This is seen as simply common sense.

Second, while this group is more likely than the rest to be relatively liberal on issues such as same-sex marriage, abortion and immigration, their views on the economy are not so left-of-centre. High earners are the most likely income group to oppose tax increases. According to both surveys and our interviews, a majority were against redistributive policies or raising taxes. Comparatively, the anti-welfare inclination of the UK’s top 10% is noticeable, along with its stronger support of meritocratic beliefs.

Michael Sandel, a professor of government at Harvard Business School, has studied the negative societal effects of belief in meritocracy in the US. For example, many young Americans are sold the message that they have won college places or landed desirable jobs on their own merit – ignoring the social and economic advantages that have helped along the way. This, Sandel observes, can corrode social cohesion because:

“The more we think of ourselves as self-made and self-sufficient, the harder it is to learn gratitude and humility. And without these sentiments, it is hard to care for the common good.”

Michael Sandel on mistaken ideas of meritocracy.

What can be done to change this mindset?

Any organisation (political or third-sector) arguing for a more liveable and equal society than the UK has now must be able to include at least some of the relatively well-off, by convincing them that greater public investment – and thus higher levels of taxation of one form or another – will benefit them too.

This demands more sociological imagination on the part of the UK’s high earners – a greater understanding both of their own position, and that the circumstances that allowed them to become high earners in the first place are not available to all.

However, appealing to any social group at a cognitive level is unlikely to work on its own, especially as the way they have carried out their lives until now, has, in their own minds, been proved correct. Most think they’re taxed enough already, that they aren’t rich and therefore the welfare state is a burden on them, and will increasingly go private.

Whether their position is based on their bottom line or their educational credentials, many have been socialised to create a distance between themselves and “others”. Yet the evidence we see of their mounting anxiety about simply remaining where they are suggests the material interests of many high earners may be changing.

The strategies they have used to propel their, until now, upward trajectories may be becoming less effective – while policies that would benefit the majority would also benefit them. These could include strengthening the welfare state, destigmatising the use of public services, demanding more from the private sector, favouring investment in public infrastructure, and taxing the wealthiest in society. However, none of these policies are currently being championed, either by the government or opposition.

To encourage greater acceptance among high earners, one framing of such policies is to envision a future in which being part of the 90% doesn’t seem so terrible after all. Writing about the US, Richard Reeves has argued that high-income earners should be OK with the idea of their children falling down the income ladder. One strand of a more cohesive future is that this prospect shouldn’t be immediately horrifying to them.

While members of the UK’s top 10% often work for and with the very highest earners in industries such as finance and management consultancy, the interests of these two groups increasingly look quite different. It is certainly unhelpful to demonise the top 10% as the main culprits for the UK’s social and economic ills.

Instead, we urgently need to encourage their greater participation in society for the future common good. As the social scientist Sir John Hills put it in his 2014 defence of the welfare state, Good Times, Bad Times:

“When we pay in more than we get out, we are helping our parents, our children, ourselves at another time – and ourselves as we might have been, had life not turned out quite so well. In that sense, we are all – nearly all – in it together.”

[Read our Comments Guidelines]